|

The Beauty of RU Exhibition of Northern Song Dynasty Ru Ware |

|

|

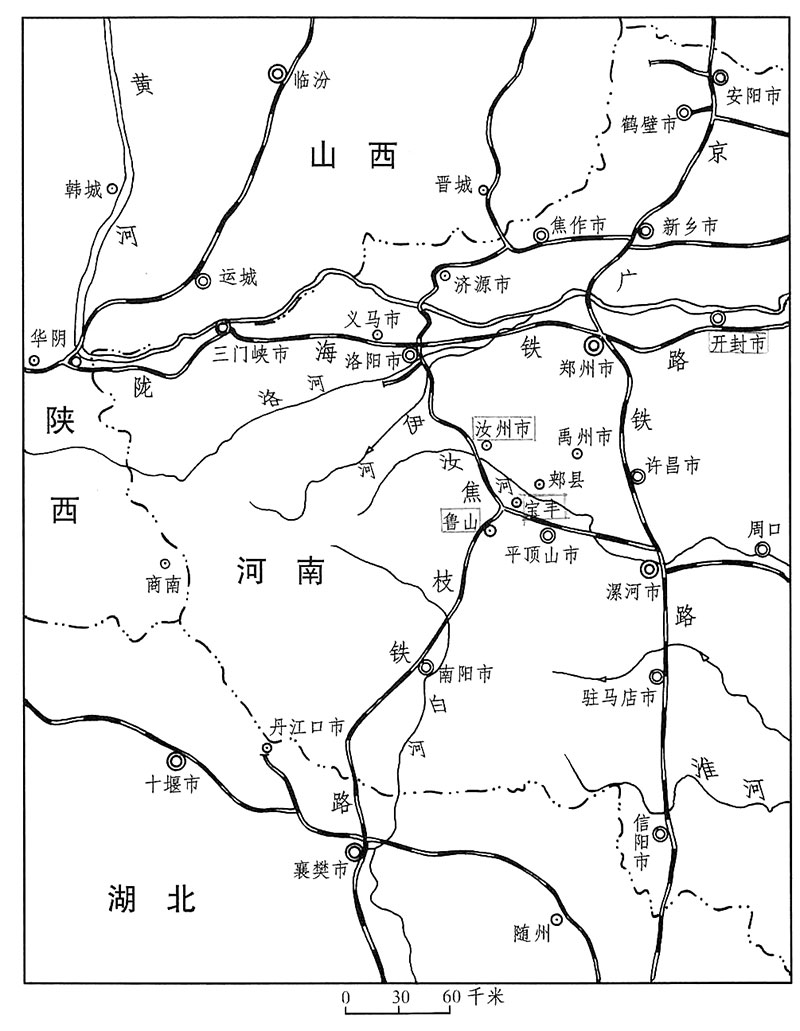

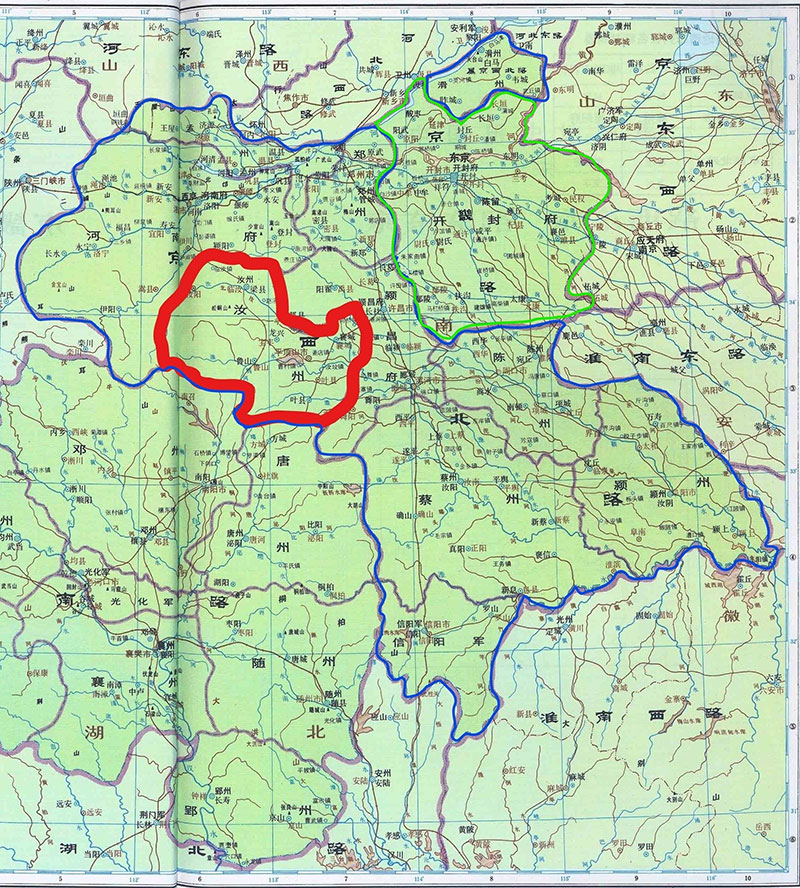

Notes on Ru and Guan Wares of the Northern Song Dynasty “Ru ware” is short for “Ruzhou ware”. In the Song dynasty, ceramics were often named after the prefectures where they were produced. For instance, those produced in the Jizhou prefecture (in present-day Jiangxi province) in the Song were called “Jizhou ware”; those in the Yaozhou prefecture (in present-day Shaanxi province) were “Yaozhou ware”; and those in Raozhou (in present-day Jiangxi province) were Raozhou ware. The ceramics produced in kilns in Ruzhou (in present-day Henan province) were thus known as “Ruzhou ware” in the Song dynasty.  Figure 1: Map of Henan province. Source: Ru Yao at Qingliangsi in Baofeng, edited by Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology (Zhengzhou: Elephant Press, 2008). Figure 1: Map of Henan province. Source: Ru Yao at Qingliangsi in Baofeng, edited by Henan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology (Zhengzhou: Elephant Press, 2008). During the Song dynasty, celadon was produced at a number of kilns within the Ruzhou prefecture, including the Linru kiln, the Duandian kiln in Lushan county, the Donggou kiln, and the Zhanggongxiang kiln, but the favourite of Emperor Huizong was the celadon from the Qingliang (r. 1101-1125) Temple kiln in Baofeng. All these can be called Ruzhou ware or Ru ware. The extant Ru ware vessels from the former Qing court now housed at the Palace Museum in Beijing, the National Palace Museum in Taipei, and other museums in the world are mostly products of the Qingliang Temple kiln, which boast exquisite quality and were highly rated by both the Song emperor and Emperor Qianlong of the Qing dynasty, thus known by some as “Ru Guan [i.e. imperial] Ware”. This nomenclature was, however, just applied in a narrow sense. In the Northern Song, regions where kilns were set up had their own “Ceramic Kiln Affairs” officials in charge of the taxation and production of ceramics.1 Should the government wish to acquire the finest products of a certain kiln in addition to the tribute ware, there were a few ways, namely “ceramics duty”, “taxation” and “advance order”.2 I have consulted with Mr. Wang Guangyao, who explains: “The ‘ceramics duty’ (shuici) is a tax-in-kind levied on the production and sales of ceramics. Under the Song taxation system, for categories of products selected for court use, 10 percent of their total production had to be submitted to the state. ‘Advance order’ (lümai or kelü) refers to official purchase orders that were planned and budgeted in advance, so that the production was sponsored by the state.“ The Ceramic Kiln Affairs officials were tasked to monitor and supervise kiln production and to oversee and screen the tribute ware. From this perspective, besides the works of the Qingliang Temple kiln, all the other high-quality ceramic vessels produced within Ruzhou can also be called “Ru Guan Ware”.  Figure 2: The Jingji (i.e. Capital) Circuit and Jingxi-bei (Jingxi North) Circuit in the Song dynasty. Source: The Historical Atlas of China (Beijing: Sino Maps Press, 1987). Figure 2: The Jingji (i.e. Capital) Circuit and Jingxi-bei (Jingxi North) Circuit in the Song dynasty. Source: The Historical Atlas of China (Beijing: Sino Maps Press, 1987). In fact, should Ye Zhi’s record in Tanzhai biheng (from the Southern Song) that “a kiln was set up in the capital for firing [Ru ware]” be proven correct one day, only the ceramics produced in the Northern Song capital, Bianliang (present-day Kaifeng, Henan province), should be considered genuine “Ru Guan Ware”. I am inclined to agree with Ye Zhi’s account. The reason behind some scholars’ doubt about the existence of a kiln in the Northern Song capital probably lies in an error in the carving of the woodblock or in the movable-type setting during the printing process. The movable-type printing technology was invented by Bi Sheng during the Qingli reign (1041–1048) of the Northern Song dynasty. A set of movable types can be reusable for the printing of different texts, since the characters can be mixed and matched, while extra types can be produced for frequently used characters and damaged types can be individually replaced. In the Southern Song period, the movable-type printing technology was already available, but most of the books were still produced using the traditional woodblock printing technique. The meaning of a text might thus have been completely distorted because of a typesetting error — assuming that the Song edition of Qingbo zazhi was a movable-type print and the printer was yet to be familiar with the new technology — or an error in the carving of the woodblock. The following four passages of Song-dynasty writings are often cited by scholars of Ru ware:

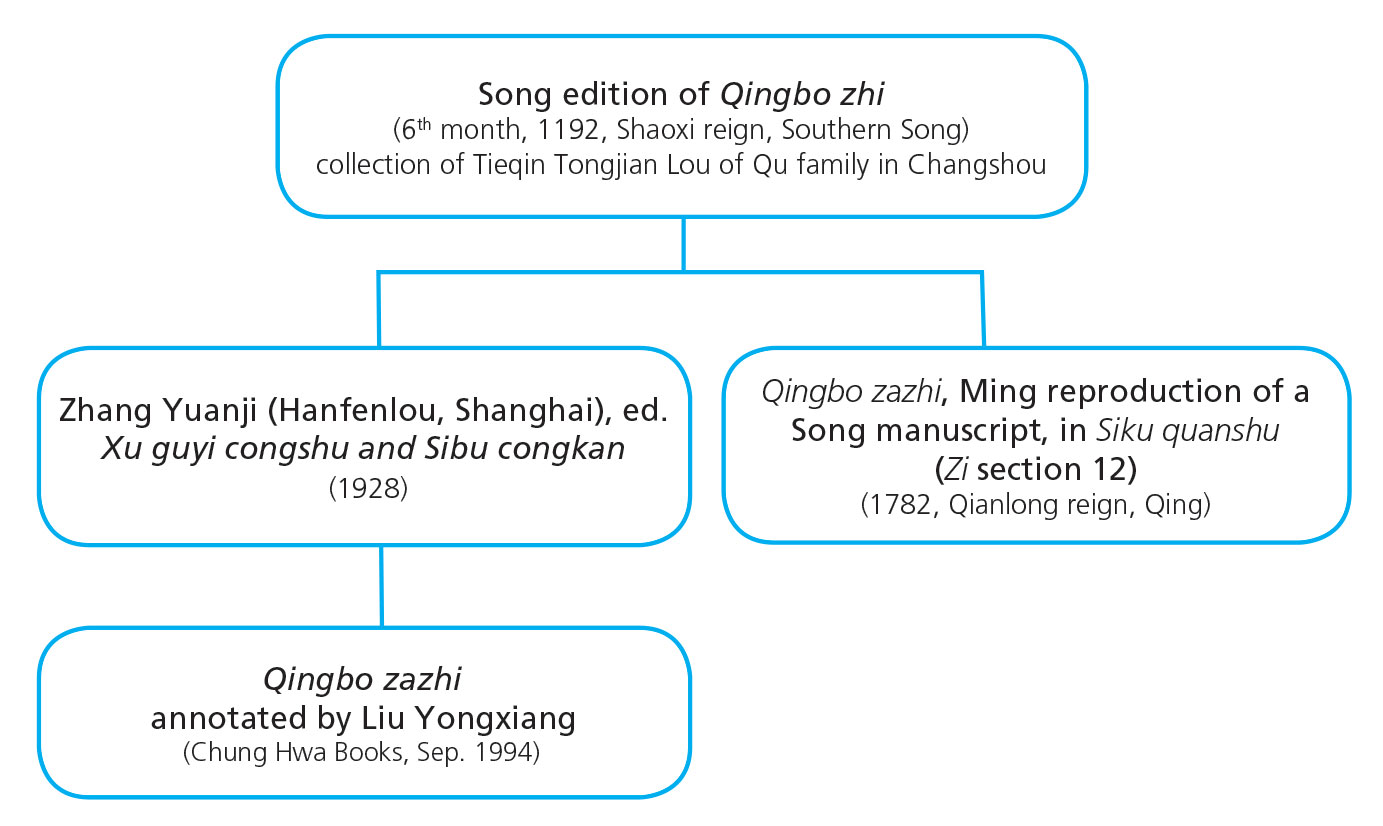

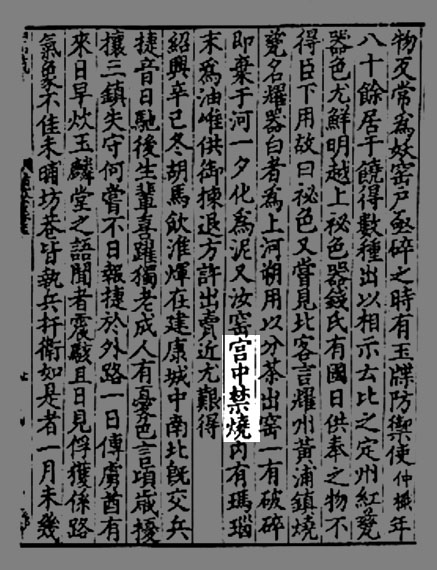

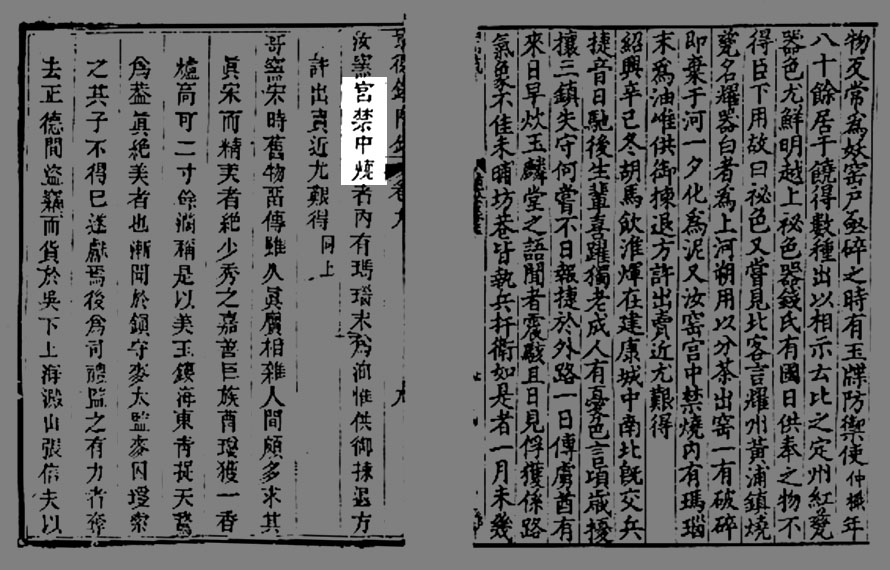

Zhou Hui, a native of Huaihai, was born in the first year of the Jingkang reign (1126); his year of death is uncertain. He passed the special decree examination for “Erudite Learning and Exceptional Literary Achievement” and had travelled to the Jin Kingdom in the north. In his later years, he lived as a recluse at the Qingbo Gate area in Hangzhou and did not venture into officialdom. His collection of books numbered over ten thousand. His works include Qingbo zazhi [Miscellanea from the Gate of Qingbo] (12 juans) and its Supplements (3 juans). For a long time, I have been puzzled by the line “The firing [of Ru ware] was prohibited in the imperial court” (gong zhong jin shao 宮中禁燒) on which scholars in the field have not really elaborated because they might think that its meaning is straightforward enough. But why was there such a ban in the court? Whether from the syntactic or semantic point of view, the original Chinese wording sounds strange. After much thought, I came up with a bold conjecture: Would this perhaps be a typographical error? Perhaps the Chinese should read “gongjin zhong shao” (宮禁中燒) instead, meaning “[Ru ware] was fired in the imperial court”. As shown in Lu You’s Laoxuean biji cited above, jinzhong (禁中) was used in Chinese in the Song dynasty to refer to the “imperial court”. Lu You’s book has another passage with the same usage: Laoxuean biji (juan1): “During the peaceful time in the capital, when members of the royal clans entered the imperial court [jinzhong 禁中] on special occasions, noblewomen in the ox-drawn carts would be flanked by two young maidservants carrying pomander balls and the women would have two small pomander sachets in their own sleeves too. As the carts passed by, wisps of fragrance filled the air for miles on end, scenting even the dust and earth.”9 Since this is a tricky matter relating to typesetting, we have to examine the relevant editions of the Qingbo zazhi, as well as their dates of publication. I am indebted to a friend of mine, formerly of the Chinese University of Hong Kong, who provided me with the two references here:

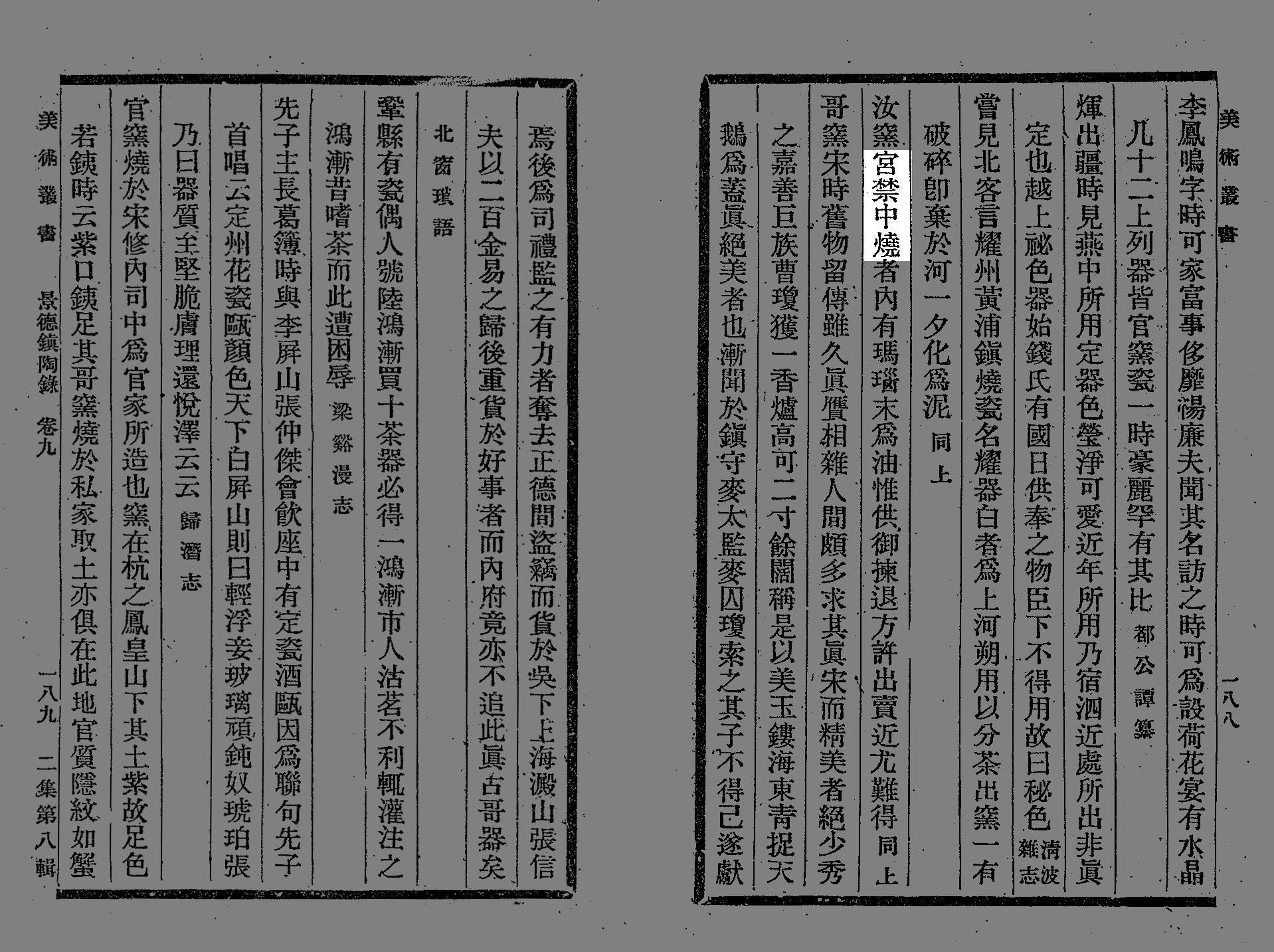

Liu Yongxiang’s Annotated Qingbo zazhi, published by Chung Hwa Books in September 1994, was based on the Sibu congkan version edited by Zhang Yuanji of Hanfenlou, Shanghai. This, in turn, was based on a printed Qingbo zhi from the Shaoxi reign (1191–1194) of the Southern Song dynasty. According to Liu’s preface, this Song version, from the sixth lunar month of 1192, was originally housed at the Tieqin Tongjian Lou (Iron Zither and Bronze Sword Studio) of the Qu family in Changshou. This was also the version reproduced by Zhang Yuanji in his Xu guyi congshu and Sibu congkan collectanea in 1928. The line does read “The firing of Ru ware was prohibited in the imperial court” (Ruyao gong zhong jin shao 汝窯宮中禁燒) in this volume too, so it is safe to conclude that the line had remained unchanged throughout the Shaoxi reign (1191–1194) of the Southern Song to the Qianlong reign (1736–1795) of the Qing times. The Siku quanshu edition, from a Ming reproduction of a Song manuscript, also has it as Ruyao gong zhong jin shao 汝窯宮中禁燒.  Figure 5: Siku quanshu (Zi section, 12) edition of Qingbo zazhi from a Ming reproduction of the Song manuscript, compiled in the Qianlong reign, Qing dynasty Figure 5: Siku quanshu (Zi section, 12) edition of Qingbo zazhi from a Ming reproduction of the Song manuscript, compiled in the Qianlong reign, Qing dynasty As Liu Yongxiang says: “Even Song editions are far from perfect. Anecdotes of the time often point to the many errors made during the printing process. And Qingbo zhi reminds us, ‘Printed words are often erroneous. Emending a book is like dusting—problems always show up as soon as you finish.’” Liu also cites a passage on Ru ware from Lan Pu’s Jingdezhen tao lu (Account of ceramics in Jingdezhen, 1815) from the Qing dynasty, which quoted the same line from Zhou Hui’s Qingbo zhi but changed it from “Ru yao gong zhong jin shao”to “Ru yao gongjin zhong shao”. Liu’s use of the expression “purported to be” (i.e. yishi, p. 215) in his annotation suggests that he is inclined to agree with Lan Pu. This gives rise to an interesting question: Was the Lan Pu reference also a typographical error, or did the scholars back then actually hold the same opinion as I do? If that is indeed the case, it shows that I am not alone!  Figure 6: Lan Pu’s Jingdezhen tao lu (1815). Source: Meishu congbian (Anthology of art), vol. 1 Pottery and Ceramics, edited by Yang Jialuo (World Book, reprinted May 1968),

juan 9, p. 188. Figure 6: Lan Pu’s Jingdezhen tao lu (1815). Source: Meishu congbian (Anthology of art), vol. 1 Pottery and Ceramics, edited by Yang Jialuo (World Book, reprinted May 1968),

juan 9, p. 188. When I was researching the topic, it suddenly occurred to me that Sir Percival David (1892–1964) read a paper entitled “A Commentary on Ju Ware” on December 2, 1936 in the Oriental Ceramic Society London. Back then he already put side by side in the Transactions of the Oriental Ceramics Society (TOCS) a page of Qingbo zhi juan 5 (written in 1192, Shaoxi reign of the Southern Song) and a page of Lan Pu’s Jingdezhen tao lu (published in 1815) where the line appears: I was, therefore, not the first one to initiate this subject on “gong zhong jin shao” and “gong jinzhong shao”. Sir Percival David argues that Lan Pu misunderstood the meaning of the passage in question in his Jingdezhen tao lu: “But the author of the Chung-te-Chen Tao Lu (Jingdezhen tao lu) misunderstands it completely, ‘edits’ it by transposing two of its characters and adding a third. The resultant passage has in consequence been taken to mean: ‘As to Ju ware, that which was baked within the forbidden, precincts of the Palace enclosure had powdered carnelian in the glaze.’ In Supplements to Qingbo zazhi in the Siku quanshu edition from the Qianlong reign (1736–1795), there are four other occurrences of the term gong zhong (宮中) and three occurrences of gongjin (宮禁):

Having said that, we still cannot rule out the possibility of “gong zhong jin shao” (宮中禁燒) being a typographical error for “gongjin zhong shao” (宮禁中燒). From the Lu You references and the 1782 Qianlong Siku quanshu edition, one can see that both gongjin宮禁 and jinzhong 禁中were commonly used to stand for the imperial court in the Song times. Should my idea, and that of Lan Pu’s in Jingdezhen tao lu, be correct, it can support the reliability of the information about Ru ware, Guan ware and Xiuneisi in Ye Zhi’s Tanzhai biheng. And from there, we can go on to infer that during the Xuanhe (1120-1125) and Zhenghe (1111-1118) reigns of the Northern Song, the court once set up a kiln for celadon ware in the capital. This type of celadon must have been a favourite of Emperor Huizong’s and similar to the excellent production from Qingliang Temple in Baofeng. Should the raw materials used at the kiln in the capital differ from those at Qingliang Temple, two products would naturally differ from each other. In other words, such Ru ware produced at the kiln in the capital, known as Guanyao (Guan [i.e. imperial] ware) in the documentary record, should look different from the products of Qingliang Temple. To determine whether this was indeed the case will require further investigations by archaeologists and scholars. However, if both the craftsmen and raw materials were sourced from Baofeng, there would be no way to tell the difference between the two. After the transition from the North to the South, the Song court set up a kiln for the firing of celadon ware under the Palace Maintenance Office (Xiuneisi) in the capital Lin’an (present-day Hangzhou) following the Northern Song system. A few specimens of “bowls with the characters guanyao (官窯, i.e. Guan kiln or Guan ware) inscribed in brown glaze on their base”10have been excavated from the uppermost (Yuan-dynasty) layer of the Xiuneisi kiln site in Hangzhou. This discovery shows that the Chinese term “Guan ware”, following the Northern Song tradition, was still applied to ceramics produced under the supervision of the local government in the Yuan dynasty. In his book, Wang Guanyao noted: “From the Song to the Ming, with the Fuliang county magistrate’s consistent supervision of the ceramic production, it would seem, at first glance, that the system of local officials being in charge of ceramics had remained unchanged throughout the Song and the early Ming times. In actual fact, it shows that official ceramic-making had continued to follow the Song system, where the local governments were under order to administer the production.”11 From the above passage, one can see that the official ceramic production system had remained basically unchanged at least in Fuliang (present-day Jingdezhen, Jiangxi province) and Lin’an (present-day Hangzhou, Zhejiang province) from the Song to early Ming. After receiving the imperial order, local officials in the ceramic production regions had to administer and supervise the firing of ceramics for court use. The Ru ware from the Qingliang Temple kiln in Baofeng was thus a product of this system in the Northern Song dynasty. Some might wonder: Why did the Northern Song court want to set up a separate Guan kiln in the capital in addition to the Qingliang Temple kiln in Baofeng, Henan? The following lines cited by Wang Guangyao from Ming huidian (Collected statutes of the Ming dynasty) may provide the answer:

Even though the above passage refers to the process during the Hongwu reign of the early Ming times, we can perhaps infer that the Northern Song court had set up a separate kiln in the capital under the same circumstances during Emperor Huizong’s reign, since the Song system of official ceramic production was still adopted till the early Ming times. K. Y. Ng

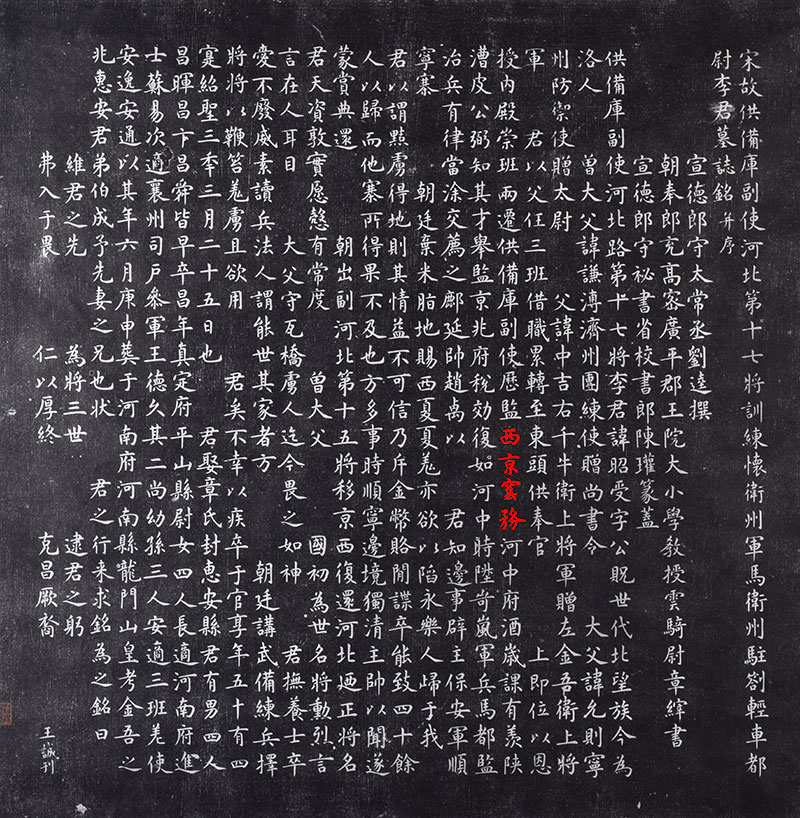

Postscript Mr. Hou Yu of the Cultural Museum of Bronze and Stone (Luoyang Jinshi Wenhua Bowuguan), Henan province, visited me during the Ru Ware exhibition and generously gave me an original ink rubbing of “Epitaph of Li, the late Vice-Commissioner of the Imperial Larder, trained under the infantry and cavalry of Huaizhou and Weizhou prefectures, Area General of Hebei Circuit Garrison 17, and Commandant of Light Chariot stationed in Weizhou” (Figure 8). The tomb’s owner Li Zhaoshou (courtesy name Gongkuang, d. 1096, i.e. 3rd year of the Shaosheng reign, Song dynasty corresponding to 1096) was a Palace Courier, twice appointed Vice Commissioner of the Imperial Larder, and eventually Director of Kiln Affairs of the Western Capital. As recorded in the “Jianzuojian”(Directorate for the Palace Buildings) entry in Song shi (History of the Song), juan 165 (Treatise on state offices, no. 5): “In the fifth year of the Xuanhe reign (1123), … Ten offices were under … the Directorate for the Palace Buildings: Palace Maintenance Office, in charge of the maintenance and repairs of the capital city and the imperial ancestral temple; … Kiln Affairs, in charge of ceramics, bricks and tiles to supply for building work and earthenware vessels.” 13 The Northern Song capital region was divided into four parts, namely the “eastern capital”—Kaifeng Superior Prefecture (present-day Kaifeng, Henan province), the “western capital”—Henan Superior Prefecture (present-day Luoyang, Henan), the “southern capital”—Yingtian Superior Prefecture (present-day Shangqiu, Henan), and the “northern capital”—Daming Superior Prefecture (present-day Daming, Hebei province). In this context, Li, who was once Director of Kiln Affairs of the Western Capital according to the above-mentioned epitaph, would be in charge of the production of bricks and tiles for building construction and the firing of ceramic vessels such as vases and jars. Neither the passages in History of the Song nor the epitaph mentions explicitly whether the Palace Maintenance Office did produce celadon ware. Nevertheless, if we can trust Ye Zhi’s record in Tanzhai biheng, officials in charge of the ceramic kiln affairs should also be responsible for overseeing the firing of celadon ware. And if imperial ceramic making in the Southern Song followed “the former capital’s (Northern Song dynasty model” and a kiln was “established under the Palace Maintenance Office for the production of celadon ware” as Ye Zhi suggests, one can perhaps just take one step back and conclude that the celadon ware was produced at the Palace Maintenance Office during the Northern Song too. According to Xu Song’s Song huiyao jigao (Draft of documents pertaining to matters of state in the Song dynasty) from the Qing dynasty, Officers 307, “The Eight East and West Imperial Works Ministries … a total of twenty-one Works Departments, namely major woodwork, … tilework, … celadon work14. ” It is unclear whether the “celadon work” was established in the east or the west capital, or in both. In any case, if a kiln for celadon ware indeed existed in the Northern Song capital, the search for the “Northern Song Guan Kiln” should probably be focused on the eastern and western capitals, in present-day Kaifeng and Luoyang in Henan province.

|