|

Tang and Song Ceramic Tea Ware Exhibition |

||||

|

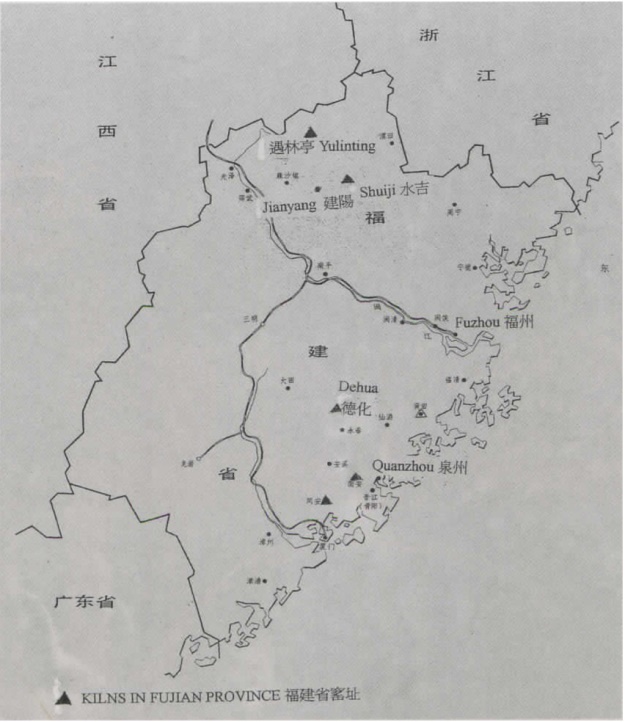

Song Dynasty Black-glazed Tea Bowls from the Yulinting Kilns at Mount Wuyi (revised basing on the article published in the Kaikodo Journal 2008, No. 24) The Yulinting 遇林亭窯 kiln-site is situated in a scenic area in Xingcunzhen in the city of Wuyishan武夷山 or Mount Wuyi in Fujian province (Fig. 1). It occupies an area of six square kilometers. Excavations in 1998 and 1999 have uncovered remnants of a porcelain-making workshop, two dragon kilns, and a number of kiln implements and porcelains. Among the porcelains are qingbai wares, black-glazed wares and celadons. Some of the black-glazed bowls bear gold and silver painted decoration and inscriptions. In Japan these are known as kinsaimojitemmoku, "Temmoku with gold painting and inscriptions," and are valued highly for use in the Japanese tea ceremony. The site is dated from the latter half of the Northern Song era to the mid-Southern Song period, roughly from the 11th to the mid-13th century, more or less coinciding with the hey-day of the Jian kilns.1 Little attention has been paid thus far to the products of this kiln, and very often its wares have been regarded as having been produced by the Jian or related kilns. The purpose of this article is to introduce these fascinating wares to the general public based on which I have learned in recent years from examining a number of pieces in public and private collections in Asia.2

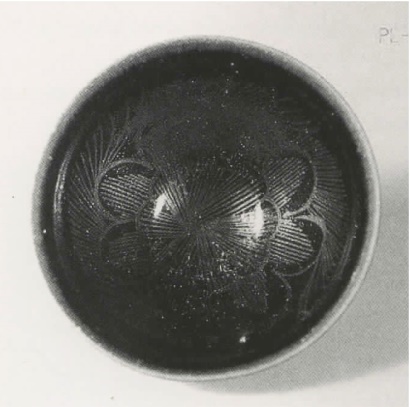

Fig. 2. Black-glazed tea bowl, Yulinting ware, llth-12th century; painted in gold with landscapes of Mount Wuyi; private collection. Mouth dia. 10.6 cm., foot dia. 3.5 cm. and h. 4.6 cm.

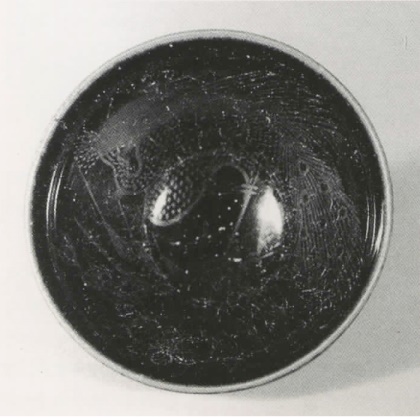

Fig. 3. Black-glazed tea-bowl with peach blossoms, bamboo and peacock painted in silver; private collection.

Fig. 4. Black-glazed tea-bowl with peach blossoms, bamboo and peacock painted in silver; private collection.

Fig. 7. Black-glazed tea bowl with gong yu long bei ("Surplus of Imperial Tribute from the Dragon Kiln") written in gold; private collection.

Fig. 8. Black-glazed tea bowl with gong yu long bei ("Surplus of Imperial Tribute from the Dragon Kiln") written in gold; private collection.

Fig. 9. Black-glazed tea bowl with "hare's fur" shou shan fu hai ("Mountains of longevity and seas of fortune") written in gold; private collection.

Fig. 10. Black-glazed tea bowl with "hare's fur" pattern and pattern in silver; private collection (see also Fig. 21).

The most important among these is the bowl illustrated in Fig. 2, a black-glazed tea bowl with inscriptions and landscapes of Mount Wuyi painted in gold on the interior. On the concave exterior wall (Fig. 13) the black glaze is a reddish-brown or soy-sauce color and, where it stops short of the foot, it reveals a grayish paste with slightly raised ridge from scraping. On the interior (Fig. 14) a rim about 1 cm. in width runs around the mouth above a recessed well in which is painted in gold the scenic spots of Mount Wuyi, namely Dongtian ("Taoist Heaven"), Youren ("Blessings on the Mortals"), Shizishi ("Lion Boulder"), Shigu ("Stone Drum"), Chong'anshui ("Waters of Chong'an"), Huizhenmiao ("Daoist Temple"), Jiuqu ("Nine Meanders"), and Hubishi ("Tiger-nose Boulder"). The architecture is drawn with straight and confident lines, what in painting proper would be termed jiehua or ruled-line drawing, comparable to the lineament seen in Fig. 10 where a Yulinting tea bowl was painted with "hare's fur" in silver. Above the landscapes in the present piece appears a row of characters written in regular script-style and recording the verse that introduces the ten poems known collectively as the Wuyi Zhoge 武夷櫂歌, "Boat Songs of Wuyi:" Up in Mount Wuyi there are divine beings, It would seem that black-glazed tea bowls in Jian style with gold painted landscapes and poetic inscriptions was a significant invention of the Yulingting kilns, and extant pieces are extremely rare. None are known at present in China proper and only a handful have been found in Japan. The piece in the Aso collection is what is termed a densei-hin 傳世品 or handed-down piece, one not recently excavated but rather treasured for hundreds of years through many generations since its arrival from the many generations since its arrival from the continent, most likely during the 13th-14th century in the luggage of some monk returning home after a period of study at the temples on Mount Tianmu.4 Another example in Japan is in the Ogura collection; this is inscribed with another of the ten "Boat Songs of Wuyi": At the first meander board a fishing boat by the side of the stream,

Fig. 13. Black-glazed tea bowl with landscape of Mount Wuyi painted in gold on the interior, see Fig. 2.

Fig. 14. Black-glazed tea bowl with landscape of Mount Wuyi painted in gold on the interior, see Fig. 2. The scenes portrayed in the centre of the bowl include: Yuci Chang'an ("Imperial Bestowed Temple"), Da Guanyinshi ("Big Guanyin Boulder"), Tiezhenren Zuo ("Immortal Tie's workshop"), Toulong Dong ("Taoist cavern to which imperial letters were delivered"), Shengzhen Yuanhua Dong ("Cavern of Taoist Heaven"), Xianhuahe ("Divine Crane Boulder") and Xiao Guanyin ("Small Guanyin Boulder").5 Zhu Xi (1130-1200) was one of the most important Chinese philosophers, a great historian, poet and essayist. He lived for many years near Mount Wuyi, where he founded a school and devoted himself to teaching and writing. When at leisure he enjoyed boating on the Jiuqu ("Nine Meander'") Stream and visiting the scenic spots in the region in the company of his friends, celebrating the beautiful landscape with poems and inscribing their works onto rocks.6 The "Boat Songs" were written in the 11th year of the Chunxi reign-era of the Southern Song, 1184, and thereafter enjoyed great popularity. The one inscribed on the bowl here is the first of the ten songs; the remainder can be found in Song Shichao, "Collection of Sung Poems." According to that source, the dedication of these poems reads: "'Ten Boat Songs of Wuyi' written as a leisure-time pleasure in the studio during mid-spring of the jiachen year of the Chunxi period (1184), to be presented to my traveling companions for their mutual enjoyment." The tea bowls with these poems can be dated no earlier than 1184 when Zhu Xi composed them and could have been created after his death in 1200. Since there were a total of ten boat songs, I believe that these tea bowls were produced in sets of ten. Extant examples of these wares in Japan with inscriptions and painting virtually identical to those found elsewhere also strongly suggest that production was not limited to single, unique sets. Painting with gold on ceramics had appeared in other wares but only rarely. A very few examples of gold-painted Ding wares from Hepei and also Jizhou wares from Jiangxi are known. Most extant examples of gold-decorated porcelains are glazed in white, reddish brown (soy-sauce or persimmon brown) or black.7 According to the ceramic specialist Ye Zhemin, "Ding wares or Ding-style porcelains with red painted motifs over a gold painted ground have been found in Liao tombs in Chifeng City in Inner Mongolia. Occasionally Ding bowls and dishes in white glaze or dark reddish-brown glaze with vestiges of gold painting are found among extant examples."8 The following examples are known to me at present:

Fig. 15. Bowl with peony sprays painted in gold on reddish-brown glaze, Tokyo National Museum. After Hasebe Gakuji: Ceramic Art of the World, vol. 12, Sung Dynasty, Tokyo, pls. 19-21.

Fig. 16. Bowl with auspicious flowers painted in gold on black glaze, Hakone Art Museum. After Hasebe Gakuji: Ceramic Art of the World, vol. 12, Sung Dynasty, Tokyo, pls. 17-18.

Fig. 17. Bowl with butterflies and peonies painted in gold on persimmon—colored glaze, Tokyo National Museum. After Song Ceramics, Tokyo, 1999, pl. 35.

Fig. 18. Bowl with water fowl painted in gold onwhite glaze, Tokyo National Museum. After Hasebe Gakuji: Ceramic Art of the World, vol. 12, Sung Dynasty, Tokyo, pls. 15-16.

Fig. 19. Black-glazed meiping vase with peach blossom painted in gold within a floral-shaped panel set on a brocaded ground; private collection.

Gold painted black-glazed Jizhou wares of the Song period are also rather few in number and are rarely mentioned in books about Jizhou wares. Among the few pieces I have seen is a meiping vase with gold painted peach blossom sprays enclosed in floral-shaped panels on a brocade ground (Fig. 19). The gold paint has largely come off, leaving only faint traces. Another example is a tea bowl with peach blossoms painted in gold (Fig. 20). Still another is a tea bowl with gold characters reading shou shan fu hai ("Mountains of longevity, seas of good fortune") in the collection of Mr. and Mrs. Yeung Wing Tak. In his Zhiya Tang zachao ("Miscellany of Hall of Elegant Aspiration"), Zhou Mi (1232-ca. 1308) of the late Song dynasty wrote: "The gold painting on Ding bowls was done with gold paste mixed with garlic juice. Gold paint thus prepared will never come off after firing."9 In modern times Ye Zhemin reported that somebody had tried this procedure but was not successful. The actual production method for the gold-painted porcelains from the Yulinting and other kilns needs further investigation. Fujian was famous for its black-glazed tea bowls, of which the "hare's fur" bowls were known to every household. Beverage prepared from powdered tea was popular during the Song dynasty. To prepare tea, boiling water was poured into a bowl with tea powder and then blended well to ensure that the tea powder was evenly dispersed. The tea powder had to be very fine, otherwise the particles would not blend well with the water. Well-blended tea powder would cling to the well of the bowl, a feature known as xiaozhan 咬盞 ("biting the bowl"). Coarse tea particles would sink to the bottom of the bowl as sediment. Pure white was considered the best tea color by tea drinkers of the Song period.10 Another miscellany of the time, the Fangyu shenglan ("Captivating views of the earth") written by Zhu Mu, says: "Tea of white color against a black bowl allows the distribution pattern of the tea powder to be more easily examined."11 The high esteem for tea of white color and the necessity to examine the sediment thus made black-glazed tea bowls most sought after at that time. But why, then, was there painting on the inside of the tea bowl in the first place? It is said that there was one monk who was able to prepare four bowls of tea simultaneously in such a way that the tea particles floating on the surface of each bowl miraculously configured themselves so as to form the characters of one individual line of poetry; the four lines appearing in the four bowls together created a single, four-line poem.12 Since not everybody could perform such ingenious tricks, a much easier way was to adorn the centre of the bowl with landscape paintings, peach blossoms, or auspicious phrases such as shou shan fu hai so as to create a delightful visual effect.It is certain that other tea bowls from Yulinting are extant but little effort has been made to locate and identify them. James Plumer, in his pioneering publication Temmoku - A study of the Ware of Chien , reported that at the Jian kiln-site he had picked up a black-glazed shard with oblique hatchings in gold, probably part of the design of a seven or eight-petal blossom in full bloom, comparable to those seen on the examples in Fig. 5 and 12.13 Dr. Robert Mowry, in his important contribution Hare's Fur, Tortoiseshell, and Partridge Feathers—Chinese Brown and Black Glazed Ceramics, 400-1400, published a black-glazed bowl in the Peter Scheinman collection that has a gold-painted dragon pursing a pearl with the character fu, "good fortune," noting that the bowl was different from the common Jian type and suggesting it came from another kiln in Fujian province.14 This is very reasonable, and I would make so bold as to attribute the bowl to the Yulinting kilns. When Feng Xianming's Zhongguo gutaoci lunwenji ("Combined Discourses on Ancient Chinese Ceramics") was published in 1987, the kiln site of Yulinting had not yet been discovered. Feng mentions in his book that three pieces of Song period black-glazed vessels with gold painting were to be found abroad.15 The first of these was probably the Dingyao bowl with butterfly and flower design on persimmon-color glaze now in the Tokyo National Museum (Fig. 17). The second, with the phrase shoushan fuhai written in gold, is also now in the Tokyo National Museum; Feng suggested faintly that this was from Jizhou. The third was probably the Yulinting bowl with landscapes and inscriptions in gold in the Aso collection discussed by Figgess. Two bowls require additional comment, the bowl painted with "hare's fur" in silver (Fig. 21; see also Fig. 10) and one with gold "hare's fur" decoration in the Kwan collection, Hong Kong. The former has a brown body while the latter has a russet-colored paste. Like typical Yulinting products, a ridge runs around the body between the lower extent of the glaze and the foot on the outer wall. But, unlike typical tea bowls from the Jian kilns, the glaze is relatively thin where it terminates on the exterior of both pieces. In his Jianyaoci ("Jian Porcelain"), Ye Wencheng says, "Usually the glaze on the outer wall (of Jian bowls) gathers at the glaze-line, forming a ring of thick glaze. On those pieces where glaze has been heavily applied, the glaze would run beyond the glaze-line to reach the base of the outer wall or the foot rim to form small globules there."16 Li Jian'an of the Archaeological Research Institute of the Fujian Museum pointed out to me that most Yulinting products have a grayish-white paste while some have a gray or deep gray paste, but there are none with russet paste; the glaze of certain small Jian bowls also runs thin where it terminates on the outer wall, and gold-painted decoration is also found on Jian products. Whether the two examples mentioned here are from the Jian or the Yulinting kilns awaits further investigation but I think they could well be products of the Yulinting kiln.

Fig. 21. Black-glazed tea bowl with "hare's fur" pattern in silver; private collection (see also Fig. 10). Very little was known about the Yulingting kiln in the past, and most connoisseurs attributed their products to other kilns. As more archaeological excavations are conducted, and more evidence comes to light, it seems certain that the ingenuity of these potters will be duly recognized. June 2007, Hong Kong *All photographs with no citation of source were taken by the author. Notes

Postscript: After the discovery of the bowl with the verse introducing the ten poems known collectively as the Nine Boat Songs of the Wuyi by Zhu Xi, which I talked about and illustrated in the article above in 2008, three more Yulinting bowls which depict the scenic spots at the 5th, the 6th and the 8th Bent of the Nine Brooks in Wuyi Mountain respectively turned up in Hong Kong market. In 2016, the Tea Ware Museum in Hong Kong acquired all the four bowls to add to their existing tea ware collection, which I think is the most appropriate place to house such a rare and interesting group of tea ware. As far as I know, there are two more tea bowls decorated with gilt landscape and poem by Zhu Xi from the Yulinting kiln in China. One is in a Canton private collection, which was published in “玩物致知” (Huanwuzhizhi, March 2009, Guangdong People’s Press, China, p.141-142), which depicts scenic spots at the 5th Bent of the Nine Bent Brook. The other one is in a Shanghai private collection, which I had seen and handled. It is also the one that introduces the Nine Boat Songs of the Wuyi Mountain like the very first one that I talked about in the above article(Figs. 2, 13 & 14). I heard that there is yet another one somewhere in North China and shards had been found in the Yulinting kiln site but I have not seen nor handled them. 15 August 2016. P.S. The above article was revised basing on the one published in the Kaikodo Journal 2008, No. 24 |

|